Rabies is infamous for its high mortality rate, with around 60,000 reported deaths each year. It’s usually contracted from infected dogs, but bats are also significant carriers in the Americas. A vital but unclear aspect of rabies is how the rabies virus (RABV) interacts with local immune cells at the site of infection. Research out of the Netherlands has focused on this interaction to understand how street strains of RABV affect human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs).

Rabies and Macrophages

Macrophages are among the first responders when a rabid animal bites or scratches a human. These immune cells can not only devour pathogens but also rally other cells to the site by releasing various chemicals like pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide. Yet, research on how macrophages interact with RABV is still in its infancy, and most existing studies have used lab-adapted RABV strains, leaving the effects of “street” strains largely unexplored.

Another interesting area involves macrophage polarization. In simple terms, macrophages can adapt to specific roles, either attacking intracellular pathogens (M1) or reducing viral clearance (M2). Prior studies have not focused on how street RABV strains might influence this polarization.

The research here zeroes in on a specific receptor – nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 7 (nAChr α7). It’s part of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP), which, when activated, dampens the immune response. The hypothesis is that RABV glycoprotein (RABV-G) may bind to this receptor, potentially suppressing the macrophage’s response.

RABV-G Binds to a Specific Receptor on Human Macrophages

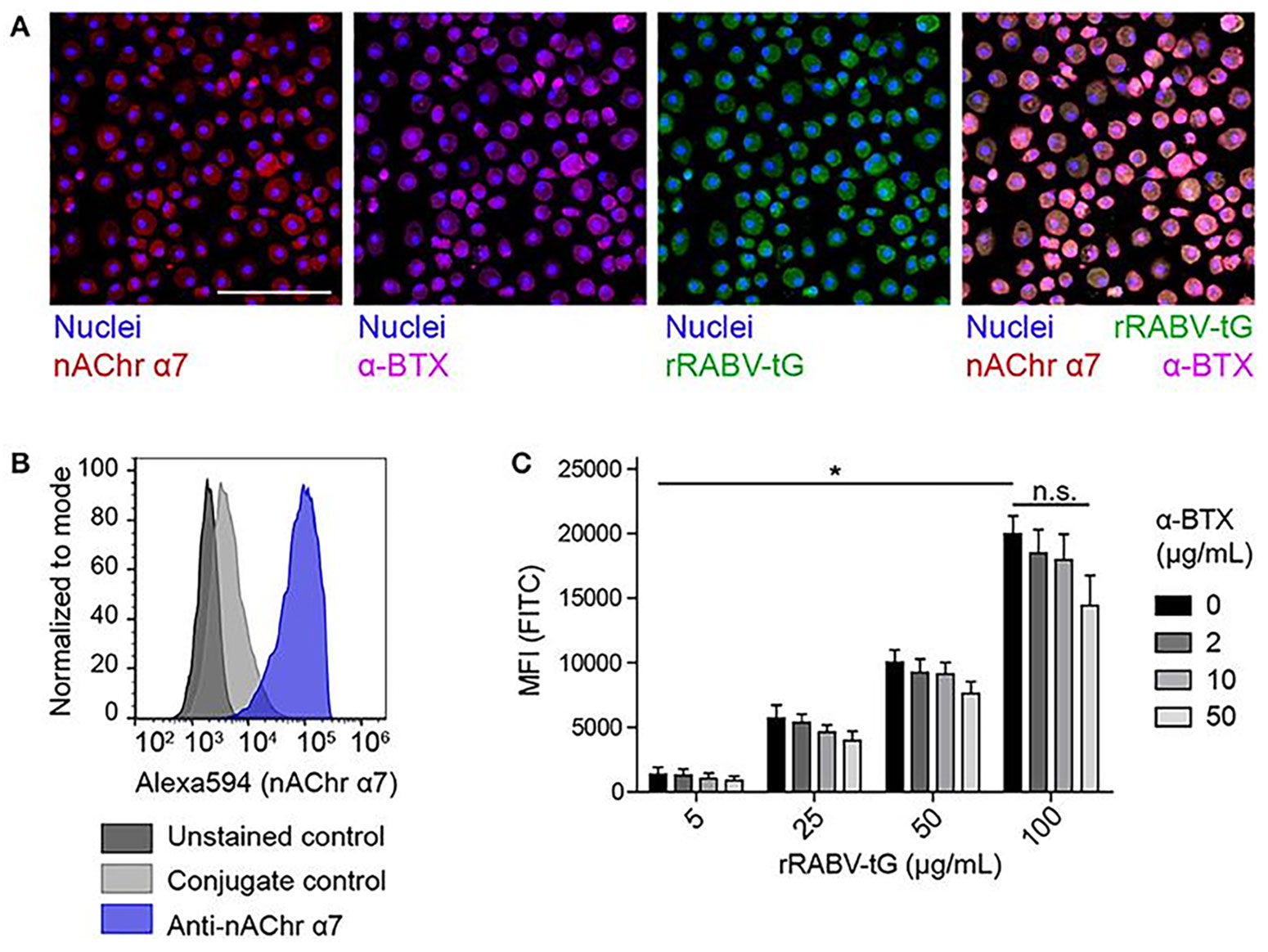

The study examined whether the RABV-G could initiate the CAP by binding to the nAChr α7 on human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs). The research team used flow cytometry and confocal microscopy to study this binding, and RABV-G’s ability to bind to human MDM via a recombinantly expressed – and FITC-labeled – trimeric form of RABV-G, based on the sequence of the Pasteur strain RABV (rRABV-tG).

Initial tests using Alomone Labs’s Anti-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α7 (CHRNA7) (extracellular) Antibody (#ANC-007) confirmed that nAChr α7 is strongly expressed on human MDMs (Figure 1). To test if RABV-G actually binds to this receptor, researchers used alpha-bungarotoxin conjugated directly to the fluorophore ATTO-633 (α-BTX; Alomone Labs, #B-100-FR), a potent antagonist of nAChr α7. Both α-BTX and labeled RABV-G were shown to bind efficiently to MDMs, suggesting that they compete for the same receptor.

RABV Glycoprotein Binds to nAChr α7 on Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages

The team then varied the concentrations of labeled RABV-G to observe its binding affinity. A clear concentration-dependent binding pattern emerged. To validate that RABV-G is binding to nAChr α7, researchers pre-treated the cells with α-BTX. Although the α-BTX didn’t completely inhibit the RABV-G binding, a decreasing trend was noted as α-BTX concentration increased, which confirmed that RABV-G does bind nAChr α7 on human MDMs.

Even though pre-treatment with the antagonist didn’t completely block the binding, it drastically reduced it. This suggests that while RABV-G has a strong affinity for nAChr α7, it can also bind to other receptors. This opens the door for further research into alternative receptors that could be targeted by the virus.

TNF-α Response and the Anti-Inflammatory Pathway

Importantly, the study also demonstrated that this binding to nAChr α7 leads to a decreased tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) response, which is a major proinflammatory cytokine. This dampening of the immune response occurs because the binding causes nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), a key factor in initiating immune responses, to be retained in the cytoplasm rather than being transported to the nucleus. Interestingly, the effect was reversible when the cells were pre-treated with α-BTX, confirming that the observed anti-inflammatory effects were due to RABV-G binding to nAChr α7.

Effects on T Cell Proliferation and Phenotype

The anti-inflammatory effects of RABV were also seen to extend to T cells. The study showed that RABV-exposed macrophages reduced T cell proliferation while increasing the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Furthermore, the researchers found that long-term exposure to RABV shifted the macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2-like phenotype, evidenced by the upregulated expression of the CD163 marker.

A Step Forward but More Questions Ahead

This research is exciting for several reasons: not only does it provide new insights into how street RABV strains interact with human MDMs, but it also opens up new avenues for developing targeted treatment strategies against rabies. However, more research is needed to fully understand these interactions, particularly regarding T-cell functions and the roles of alternative receptors.

What is clear from this study is that understanding the interaction between RABV and local immune cells is critical for developing more effective post-exposure treatments. As rabies continues to be a significant global health issue, studies like this are crucial steps forward in managing and eventually eradicating the disease.

Antibodies

- Anti-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α7 (CHRNA7) (extracellular) Antibody (#ANC-007)

- Anti-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α7 (CHRNA7) (extracellular)-ATTO Fluor-633 Antibody (#ANC-007-FR)

- Anti-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α7 (CHRNA7) (extracellular)-FITC Antibody (#ANC-007-F)

Blockers – Venom Peptide Toxins

Explorer Kits & Research Packs

Explorer Kits

- nAChRα Antibody Explorer Kit (#AK-231)

- nAChR Antagonist Explorer Kit (#EK-205)

- nAChR Modulator Explorer Kit (#EK-202)

- nAChR Antibody Explorer Kit (#AK-203)

- Muscle Specific nAChR Antagonist Explorer Kit (#EK-207)

Research Packs

- Muscle-Type nAChR Basic Research Pack (#ESB-900)

- Muscle-Type nAChR Premium Research Pack (#ESP-900)

- Muscle-Type nAChR Deluxe Research Pack (#ESD-900)